Introduction Part II | mnemofs

We'll dive into an incremental explanation of various concepts involved with file systems and operating systems. It dives into a lot of "suppose" and "what ifs" to try and get you a sense of the problems that lurk in plain sight. Only by recognizing the existence of these problems can people begin to think about trying to solve them.

Solutions exist

only after problems

are identified.

- Me, 2k24File Systems and Operating Systems

If you develop your own OS, and if you develop your own file system (FS), and if you only want your own FS in your OS, then you can develop them pretty much however you like them. Your OS can change to suit your FS needs, or vice versa. There is no need to be considerate of users or other developers who differ in opinion. Make your own OS-FS pair if you are so much better! There is no need to be the most efficient! If it gets the job done, it is good enough!

This "true power" is probably what was felt by the developers of DOS decades ago.

The world has changed since then. For better or worse, it has become too complex and demanding for one solution to be efficient or even sufficient for all needs out there. If you're a FS developer, not only is there someone out there who might do it better, but you also need to tailor your FS to support a very specific subset of storage devices and technologies to be efficient in that subset of storage technologies.

Virtual File Systems (VFS)

Why?

Let's say I am an OS developer, and my under-development OS has this file system that I have named abcdfs, and I have to make my OS interact with the FS using the methods that my FS exposes, like:

int abcdfs_open_file_from_path(char *path);

int abcdfs_close(char *path);

int abcdfs_del_file_but_actually_it_duplicates_the_file_instead_sike(char *path);In such a world, if I am developing my own OS-FS pair, my FS doesn't really have a hard boundary on what it can or cannot do. It can try and access the internet, send an email, run your game, etc.

Can you see the problem? The implementation of the communication between an OS and FS would change depending on the FS. No standardization, a free but chaotic mess.

Also, early on, in the 1980s, with the rise of a lot of FSs that seemed to be more or less similar to each other, there was a rise of the opinion that an OS should allow users to choose their preferred file system.

A nightmare if you combine the problems.

So the OS developers put some restrictions on the FS developers in the form of standardization. Wherever there is standardization, there are restrictions, but also flexibility in choosing solutions.

What?

A Virtual File System (vfs) is basically a simple interface that the OS demands an FS implement. This allows the OS to use multiple file systems at once, and execute the necessary ones.

For example, if an OS defines its interface to be like this:

struct vfs_ops {

char (*open)(char *),

char (*close)(char *),

};then it means that it wants every file system to have at least one open and one close function. The file systems can then expose it like:

struct vfs_ops abcdfs_vfs_ops = {

.open = abcdfs_open_file_from_path,

.close = abcdfs_close,

};This interface is what the OS will use to interact with the file system. If a user wants to open a file, then the OS can expose a system call like int open(char *path) for the user. The internal implementation can be over-simplified to this:

int open(char *path)

{

// headache stuff

struct vfs_ops ops = get_vfs_ops_from_path(path); // ops == abcdfs_vfs_ops

ops->open(path);

// even more headache stuff

}This has some obvious advantages:

- The user does not need to care about the underlying FS being used.

- The FS developer does not need to develop their own OS.

- The FS developer just needs to modify their existing FS to include the interface of the OS they want to run their FS on.

Drivers and Operating Systems

Without diving into too much detail, a lot of OSes also have an interface similar to a VFS for device drivers, which includes drivers for storage devices.

Now the FS developers do not have to explicitly support a very specific storage device from a very specific manufacturer, but can become more generalized. Instead of making a FS that supports only Samsung 1TiB SSDs, I can move on to making an FS that instead, say, supports only SSDs, leaving the implementation details to the drivers provided by the manufacturers.

Again, redistribution of pain.

So, in a way similar to the communication between OS and FS, the FS can now interact with the storage device through the OS using their respective interfaces, like:

int abcdfs_open_from_path(char *path) {

// code

struct device dev = get_device_from_path(path);

if(device_type(dev) != STORAGE_DEVICE) {

return -EINVAL;

}

struct storage_driver_ops ops = get_storage_driver_ops_from_device(dev);

ops->read_at_offset_in_bytes(offset);

// more code

}Entire Flow

Let's go over the entire flow.

A storage device is connected to your computer or machine, and the CPU can communicate with it using the driver it provides (not going into too many details of this part here as it deals with hardware I/O).

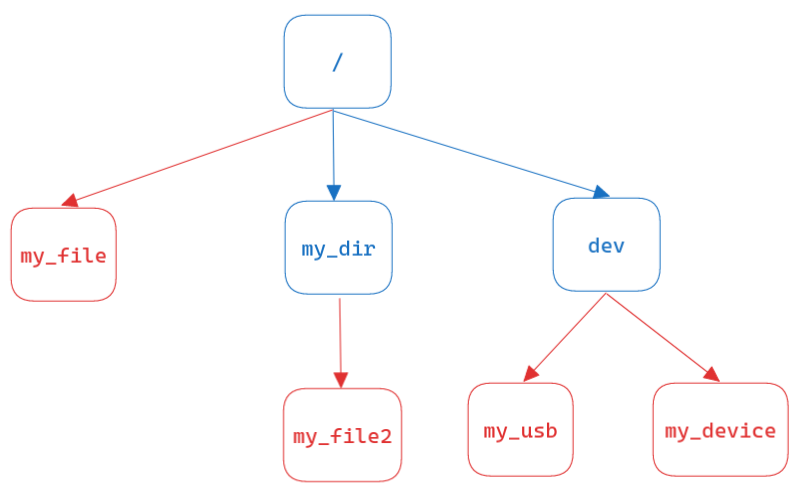

Your OS will have that one FS it supports internally. It is upto the OS developer, and can be anything...rootfs, fat32, etc. This maintains a global hierarchical system from the root /. Due to the whole "everything in Unix is a file (opens in a new tab)" thing, your device may be visible as a device in with a path like /dev/my_device. Again, it exploits the whole VFS-is-just-an-interface thing. As long as it is follows the interface, it can still do pretty much anything on your OS, given enough permissions. A free, but not chaotic, mess 🥳.

If you want to use this device with a file system, you need to mount it. So, this storage is then mounted at a certain location in your computer's location, say, /hi. This process involves mentioning the file system that you want to mount this device with, say abcdfs. This creates a directory /hi, which will now serve as the root for this storage device. The metadata about the mount process is stored by the OS (where it is stored is implementation-dependent).

Now, when a user wants to, say, create a file /hi/my_file3, they will call the required system call (syscall) that the OS provides for creating a file at a given path. Inside this syscall, the OS will try to create a file /my_file3 on the storage device mounted at /hi. It will get the VFS operations of the file system that was used to mount the device at /hi and use the create method exposed by that file system to create that file.

The create method exposed by the file system might itself use a write function exposed by the driver of the storage device through the mount point. A mount point contains information about the file system and the device, and thus, both the device's driver operations and the file system's operations can be used through the mount point.

This is a very simplified and generalized way in which OS, FS, and devices interact with each other.

Conclusion

Here we learnt how FS interacts with the OS, and in Part III, we'll dive into FS and the various solutions that have emerged through the decades to an apparently "simple problem."

⌂ Home

MIT 2024 © resyfer.