Mnemofs Least Recently Used (LRU) Cache

Before diving into the LRU Cache, called LRU for short, we need to look into a data structure that every one seems to know, but with a slightly different flavor.

Kernel Linked Lists

Linux, and NuttX (among others) have this very special flavor of linked lists that seem to make it just right, called a kernel linked list, or simply, a kernel list. This is a circular doubly linked list which can be used to store any data type.

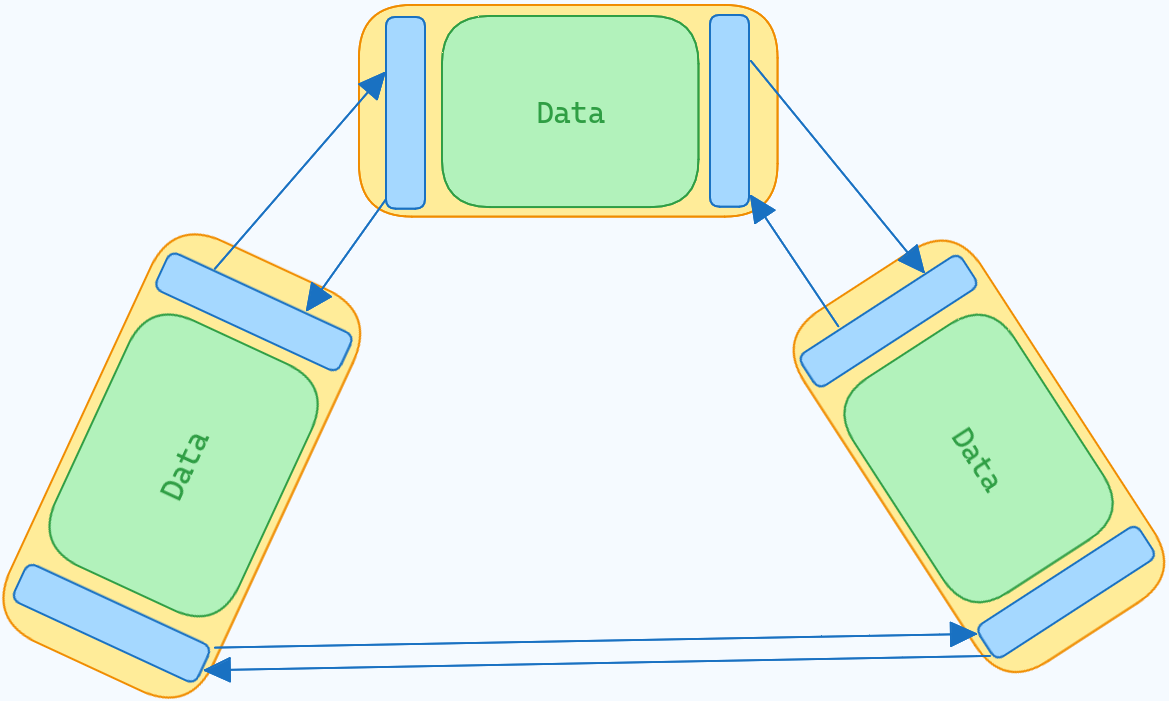

Below is a traditional circular doubly linked list.

And the below is a kernel list.

The type struct list_head contains only pointers to other struct list_head. It doesn't care about the structure it is part of. This can allow traversal, and conversion of any kind of structure we want into a list. The question is, if we have a pointer, how do we get the original structure back?

The answer to that is pretty simple and brilliant. Pointer offsets. If your struct struct my_struct contains a member struct list_head list, then, let's say, the offset of list from the start of the struct is off, then if we have an address x pointing to list, we can get its parent by just doing x - off. off will always remain constant for a given struct, and there are utilities provided to calculate them. In fact, the list utilities don't require you to even have to think too much about how this works.

LRU structure

Back to the LRU. The LRU is in-memory, and its main purpose is to reduce the wear of your storage device. The way it does is by bunching some changes to the same file, and then writing them all in one go. LRU bases itself off of the structure of a traditional LRU design, and so, like any good LRU, it needs a doubly linked list implementation. We'll go a bit further than that and use kernel lists.

The LRU in mnemofs is a kernel list of nodes. Each node represents a file or a directory. Each node contains deltas, which are basically the updates a user wants. The deltas are arranged in a kernel list for code reduction, however, they may use something as simple as a singly linked list. Deltas are of two types: either put x bytes at an offset off by replacing at maximum x bytes (less than x bytes at the end of a file), or delete x bytes from offset off.

When a new node is to be inserted, and if the LRU is full, the last node (tail of the list) is popped off, and all the deltas in it are written to the flash. This is called the flush operation. A flush operation may happen implicitly as explained, or explicitly in cases like where a file is closed.

When the deltas are written to the flash in an Copy-On-Write (CoW) manner, the new location and size is changed and the journal comes into play here. This need to be updated in the parent as well. Thus the parent goes through this same procedure for updates as well.

CoW file systems face a very common problem of cascading or bubbling up of updates. If a file is updated, its location changes. Thus the parent needs to be updated, and its location is changed as well, and so on this rises up the file system till the root is updated. However, unlike most CoW systems, the LRU does not let the updates bubble up into the file system immediately.

The LRU isn't a cache in a strict sense, as the original data still needs to be read from the flash before applying the changes to the LRU, and thus, does not "save" time like usual caches. However, the main purpose it has is to batch updates together to reduce the number of times the file is updated in the flash. The size of the LRU is configurable during compile time, thus giving control over the RAM vs wear tradeoff. Also, if someone wants to apply the updates to the flash as soon as possible, then the LRU size should be kept to a minimum.

Unlike traditional caches, we're quite happy to use the fact that while using caches, the original store is not up to date with the in-memory store as this stops (or rather, staggers) the upward propagation of the updates to the root. My apologies to all those great people who have worked to solve this issue in other areas of computing.

Power loss will cause all changes in the LRU to be lost. In fact, it's the only bunch of updates that will be lost. The updates in the journal will remain, and the file system will be in a recoverable state at all times.

The smaller the LRU is configured, the lesser you will lose after a power loss.

Applying updates

When it's time to update convert the deltas into actual data on the flash, it's pretty complicated. The first task is to determine what doesn't need to change. If a file takes up blocks a, b, c, d and if the block c has some deltas, then the new blocks have to be like a, b, x, y due to CoW. Thus, the "prefix" needs to be determined, which, in this case, is a, b blocks.

Now, we need to apply all updates contained in the deltas over such a file. Due to the limitation of the types of deltas, this gets much simplified into a two pointer method, where the upper limiter of the window shifts inwards by x bytes for every deletion that shifts x bytes inside the window. It might shift x + y bytes in total, where y bytes fall outside the window. The way this two pointer window algorithm works, y will not be lower than the minimum limiter of the window, but rather, can only be higher that the upper limiter. We do not care about this, as the next iteration will take care of it. Also, we increment a deleted bytes counter...say del...by x to denote how many bytes have been deleted before the start of the window. So, then, if we are considering a window x, x + m in the new file, then we need to copy the bytes x + del, x + m + del from the old file. This way del marks the amount of "compensation" we need to provide.

After the window reaches the end of updates, it's time to save this new location in our journal.

⌂ Home

MIT 2024 © resyfer.