Computer Boot Sequence with BIOS

(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)

When the power button is pressed, the motherboard initialises its own firmware (chipset, etc.) and gets the CPU running.

NOTE: If the CPU is dead or missing, the system is just a dead system with only mechanical parts like fans and any small motherboard diodes working working. Some motherboards have beeps to signal such failures, but most are like this. At times a faulty peripheral can cause this issue, so removing all non-essentials can help isolate the issue.

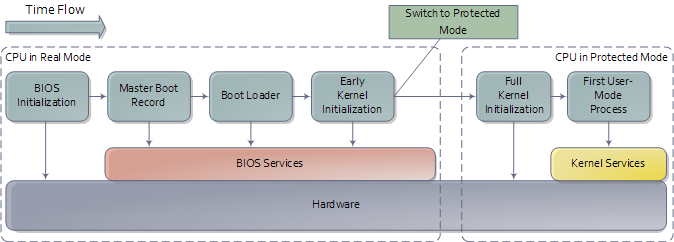

Then the CPU starts the boot processes. In multiprocessor systems, one processor is chosen to be the bootstrap processor (BSP) while the others become application processors (AP) and remain halted. This BSP runs in real-mode, behaving very much like the old Intel processors like 8086 (especially since all Intel CPUs are fully backward compatible). In real-mode, it can only use 1 MB on memory, and memory paging is disabled, and there is no notion of protection or priviledge.

Reset Vector

Most CPU registers have pre-defined startup values. For example, the instruction pointer (EIP) has a startup value of 0xFFFFFFF0 (4GB - 16B) . For the case of EIP, even though the processor runs in real-mode on boot, this value is loaded through a hack of a hidden base address this register has. Essentially it's loading in the offset 0 at the base address 0xFFFFFFF0, and it's the 0 that needs to fall inside the 1MB rule.

This location is called the reset vector and is a standard across Intel CPUs. It's the motherboard that ensures that instruction at reset vector is a jump to entry point of BIOS. This jump also (implicitly) clears the hidden base address of EIP. The motherboard knows the BIOS entry point as it has the memory map in the chipset.

Power-On Self Test

The CPU then starts executing BIOS. The BIOS then starts executing the Power-On Self Test (POST) which basically health checks various hardware components. If any health check fails, there are errors. Especially when the video card fails, the motherboard resorts to the beeps since you can't display anything as it's the video card failing.

Thus, the video card is tested, following which display is good to be used. Thus, now you get the manufacturer logo, etc. Then, the memory and other devices are tested, and errors in these cases are printed to the screen.

POST is both testing and initialisation. This also includes resources like interrupts, memory ranges and I/O ports for PCI devices. Modern BIOSes follow the ACPI and build a lot of tables that describe the devices in RAM, and can be used by the kernel later.

The BIOS then looks at the configurable boot-order to boot up the operating system. The OS may be present in one of the configured non-volatile memories. Failure to find any suitable candidates, it throws the “Non-System Disk” or “Disk Error”.

Disks, Sectors, Partitions and Boot

Sector 0

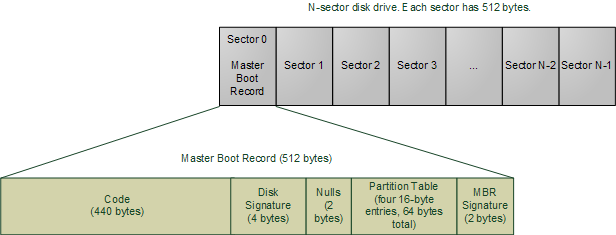

The BIOS reads the first 512-byte region from a disk. These 512-byte long divisions in disks are called sectors. The first sector of a disk, or sector 0, is entirely loaded by the BIOS to 0x7C00 (31 KB) in main memory and the execution starts from there.

MBR

While the BIOS does not care about the code inside these sectors, in Master Boot Record (MBR) partitioning, it has a very tiny OS-specific bootstrapping program (440 bytes maximum), and also has a partition table which can at max hold 4 partitions with each entry being 16-byte long, plus some signatures.

NOTE: The BIOS REALLY doesn't care about the code contents, and it can even be a virus 🙂.

The code could be OS bootloaders like Windows MBR, Linux bootloaders like GRUB, LILO, etc. As said above, any software. However, to be the most useful, the software should technically boot an OS.

GPT

Most modern computers use GPT partitioning(6) which overcomes the 4 partitions limitation of MBR.

Boot Sector

Traditionally, something like the Windows MBR (living in disk's sector 0) will look at the (only) partition in the partition table marked active, load the first sector that partition, and execute the code. The first sector of such a partition is called the boot sector. This is NOT sector 0, which is the first sector of the disk. This is the first sector of a partition on that disk. There are multiple partitions on a disk.

The errors that can be received are thrown out by the MBR, and are thus, MBR-dependent.

Modern Boot Loaders

Modern boot loaders like GRUB are more sophisticated than just booting the “active” partition. The MBR of the disk will just contain the first stage of the bootloader (GRUB names it “stage 1”). The MBR code is very tiny in size, 440 bytes. There is a lot to do in those 440 bytes:

- Determine boot partition

- Determine kernel image location on boot partition (either by a fixed image location or reading the file system)

- Load kernel image to memory

- Prepare kernel runtime (eg. stack, etc.)

These need to be done, not specifically in that order. Thus, there needs to be some sort of way to load even the boot loader and then the kernel. There are various ways like:

- Geek loading : Squeeze everything into 440 bytes, not recommended as side-effect is being feature-less.

- One-stage loading : Jumps to start of kernel, the first 1 MB is loaded due to real-mode. That contains the stub program that switches to protected-mode, does the above stuff, and jumps to kernel main.

- Two-stage loading (used by GRUB): Stub is separate, loaded below 1 MB memory mark, and does everything from above and jumps to kernel main.

So, the size is just enough to load some other sector for additional boot code. This might be another boot sector, or even some other partition that was hard-coded in the MBR code.

Thus, we have the entire bootloader in memory now. In GRUB this is Stage 2, while in Windows, this is C:\NTLDR. Then this bootloader reads the configuration file which is grub.cfg for GRUB and boot.ini for Windows (NOTE: Windows 10 has replaced this with Boot Configuration Data.(7)).

Windows goes ahead with the boot, but GRUB presents the choices for OSes to the user.

Another controversial thing to note is GCC only generates protected-mode executables according to OSDev Wiki. BUT StackOverflow says a flag -m16 is present to tell GCC to compile 16-bit code.(8)(9)(10)

Booting Kernel

At this stage, after the OS is selected by user in GRUB (or you know what OS you're booting as in the case of Windows), it's time to load in the kernel.

When it comes to GRUB, it needs to read about the partitions present, loads the required module (filesystems, partition format , etc.), and it's read from the file named like vmlinuz-xyz, and jumping to the kernel bootstrap code (kernel entry point). Windows has some of that already in NTLDR. NTLDR loads the kernel image ntoskrnl.exe present in System32 and jumps to the kernel entry point.

For information:

❯ ls /boot

drwx------ - root 1 Jan 1970 efi

drwxr-xr-x - root 4 Feb 18:56 grub

.rw------- 148M root 7 Feb 01:14 initramfs-linux-cachyos-bore-fallback.img

.rw------- 24M root 7 Feb 01:14 initramfs-linux-cachyos-bore.img

.rw-r--r-- 8.1M root 12 Nov 2024 intel-ucode.img

.rw-r--r-- 15M root 4 Feb 18:55 vmlinuz-linux-cachyos-bore❯ stat -f -c "%T" /boot/vmlinuz-linux-cachyos-bore

xfsThis is formatted in the format I had mentioned for root partition while installing linux. Here are the partitions:

❯ lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

sda 8:0 0 931.5G 0 disk

├─sda1 8:1 0 16M 0 part

├─sda2 8:2 0 531.5G 0 part

├─sda3 8:3 0 8G 0 part [SWAP]

└─sda4 8:4 0 392G 0 part

└─luks-f39ba5ac-f9b2-4f38-aa1d-4ed28a47cb07 253:0 0 392G 0 crypt /home

zram0 254:0 0 7.5G 0 disk [SWAP]

nvme0n1 259:0 0 238.5G 0 disk

├─nvme0n1p1 259:1 0 500M 0 part

├─nvme0n1p2 259:2 0 128M 0 part

├─nvme0n1p3 259:3 0 157.9G 0 part

├─nvme0n1p4 259:4 0 512M 0 part

├─nvme0n1p5 259:5 0 512M 0 part /boot/efi

├─nvme0n1p6 259:6 0 64M 0 part [SWAP]

└─nvme0n1p7 259:7 0 78.9G 0 part /The important parts are sda4 for my /home, nvme0n1p7 for root (where the /boot/vmzlinuz-xyz file lives), nvme0n1p5 (where /boot/efi lives) and just a swap partition for nvme0n1p6.

It's interesting that while /boot is in root partition, /boot/efi is not. It's a separate partition, and is just mounted as such to the root file system.

❯ sudo ls /boot/efi

[sudo] password for resyfer:

EFI 'System Volume Information'Consequently if you try to checkout the /boot/grub folder for the various files (like grub.cfg), you find something like (interesting ones are put):

~

❯ tree /boot/grub

/boot/grub

├── fonts

│ └── unicode.pf2

├── grub.cfg

├── grubenv

├── locale

│ ├── ast.mo

│ ...

│ ├── uk.mo

│ ...

├── themes

│ └── starfield

│ ├── blob_w.png

│ ...

└── x86_64-efi

├── acpi.mod

...

├── fat.mod

...

├── hello.mod

...

├── linux.mod

...

├── ls.mod

...

├── mmap.mod

...

├── msdospart.mod

...

├── multiboot2.mod

├── multiboot.mod

...

├── ntfs.mod

...

├── part_msdos.mod

...

├── password.mod

...

├── terminal.lst

...

├── terminfo.mod

...

├── usb_keyboard.mod

├── usb.mod

...

├── video_colors.mod

...

├── video.mod

...

├── xfs.mod

...

6 directories, 358 filesGRUB's config file can be created using its os-prober, as it's also written at the start of the grub.cfg file that it's autogenerated:

❯ sudo cat /boot/grub/grub.cfg

#

# DO NOT EDIT THIS FILE

#

# It is automatically generated by grub-mkconfig using templates

# from /etc/grub.d and settings from /etc/default/grub

#

### BEGIN /etc/grub.d/00_header ###

...The file systems present as the modules are attached to various GRUB settings, for example, if you go lower into the file:

### BEGIN /etc/grub.d/10_linux ###

menuentry 'CachyOS Linux' --class cachyos --class gnu-linux --class gnu --class os $menuentry_id_option 'gnulinux-simple-b6f3c148-6dd2-4be8-9d22-fec5fc2ba25d' {

load_video

set gfxpayload=keep

insmod gzio

insmod part_gpt

insmod xfs

search --no-floppy --fs-uuid --set=root b6f3c148-6dd2-4be8-9d22-fec5fc2ba25d

echo 'Loading Linux linux-cachyos-bore ...'

linux /boot/vmlinuz-linux-cachyos-bore root=UUID=b6f3c148-6dd2-4be8-9d22-fec5fc2ba25d rw nowatchdog nvme_load=YES zswap.enabled=0 splash resume=UUID=722266aa-b24a-472c-bdf4-158e9a3e1f23 loglevel=3

echo 'Loading initial ramdisk ...'

initrd /boot/initramfs-linux-cachyos-bore.img

}A superficial look shows that gzio, part_gpt and xfs modules are loaded for GZIP, GPT partitioning and XFS file system (my formatted file system for root), and then the OS.

Loading Kernel Image

So, while all this is happening, the CPU is working in real-mode. This means it has a maximum of 1 MB physical address space. But most OS kernels are pretty big… more often bigger than 1MB. For reference, an Ubuntu kernel from 2008 is around 2 MB long. This is a problem with respect to loading the OS kernel in the RAM, as they are bigger than the addressable limit.

Here, the unreal mode(5)(11) comes in. It's not an actual mode, but it refers to switching between real-mode and protected mode as and when required. For example, protected-mode for loading image, but real-mode for other hardware-related stuff.

GRUB

The bootloader that's preferable is GRUB. It's an easy way out compared to the alternative of creating our own bootloader. It supports a lot of file systems, and also supports loading in generic ELF executables instead of flat binaries like other bootloaders.

Bootloading has evolved over the years, and even Linux has undergone changes to reflect this evolution. Old Linux used to boot from a floppy disk, and loaded the first sector as “raw”, ie., without a file system. The following sectors had startup for various devices (similar to POST). And then it loaded the compressed tarball containing the kernel.

References

- (1): https://web.archive.org/web/20190228193647/https://manybutfinite.com/post/how-computers-boot-up/ (opens in a new tab)

- (2): https://web.archive.org/web/20190402174801/https://developer.ibm.com/articles/l-linuxboot/ (opens in a new tab)

- (3): https://wiki.osdev.org/Boot_Sequence (opens in a new tab)

- (4): https://coreboot.org/ (opens in a new tab)

- (5): https://wiki.osdev.org/Unreal_Mode (opens in a new tab)

- (6): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GUID_Partition_Table (opens in a new tab)

- (7): https://www.tenforums.com/general-support/175284-where-does-w10-store-equivlent-boot-ini.html (opens in a new tab)

- (8): https://sourceware.org/binutils/docs/as/i386_002d16bit.html#i386_002d16bit (opens in a new tab)

- (9): https://stackoverflow.com/a/33022889 (opens in a new tab)

- (10): https://stackoverflow.com/questions/19055647/how-to-tell-gcc-to-generate-16-bit-code-for-real-mode#comment53870969_19064127 (opens in a new tab)

- (11): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unreal_mode (opens in a new tab)

⌂ Home

MIT 2024 © resyfer.